The Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Motifs 1, 2 and 3

Part of

A Study of Basketmaker III Black-on-white Bowl Motifs in the Four Corners Region

by Linda Honeycutt

Talk presented at Society for American Archaeology Annual Meeting April 2019 Albuquerque, New Mexico

Introduction

My talk today is about the temporal and spatial distribution of Motifs 1, 2 and 3. To begin, I'd like to provide a bit of background on my project and on these three motifs.

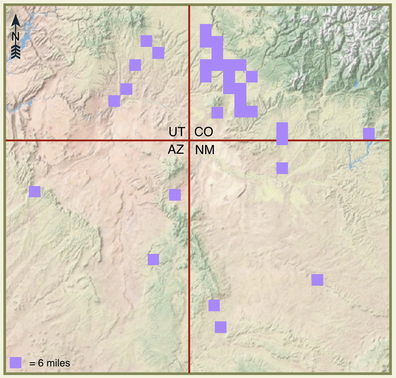

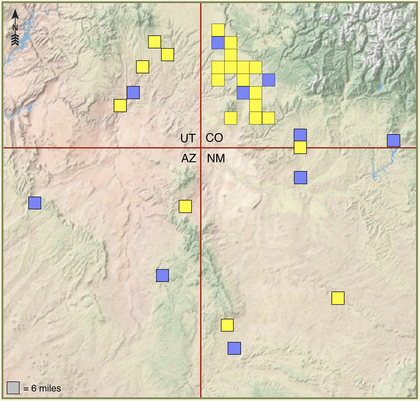

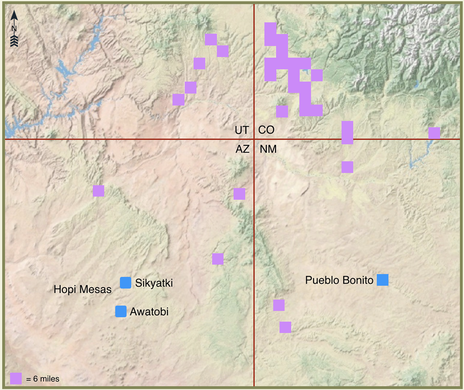

My research has been on-going for ten years, during which time I have identified nine Basketmaker III black-on-white bowl motifs. My database contains records on approximately 2,400 photographs of bowls and bowl sherds from 108 sites which were scientifically excavated and documented. These photographs were take at, or obtained from, 15 museums in the United States. As shown in Figure 1, the locations of the 108 sites can be represented by 32 study units, each measuring six miles square. The results of my research are posted on my website Basketmaker III motifs.org.

Figure 1. Map showing location of 32 project study units in the Four Corners Region.

Motif Overviews

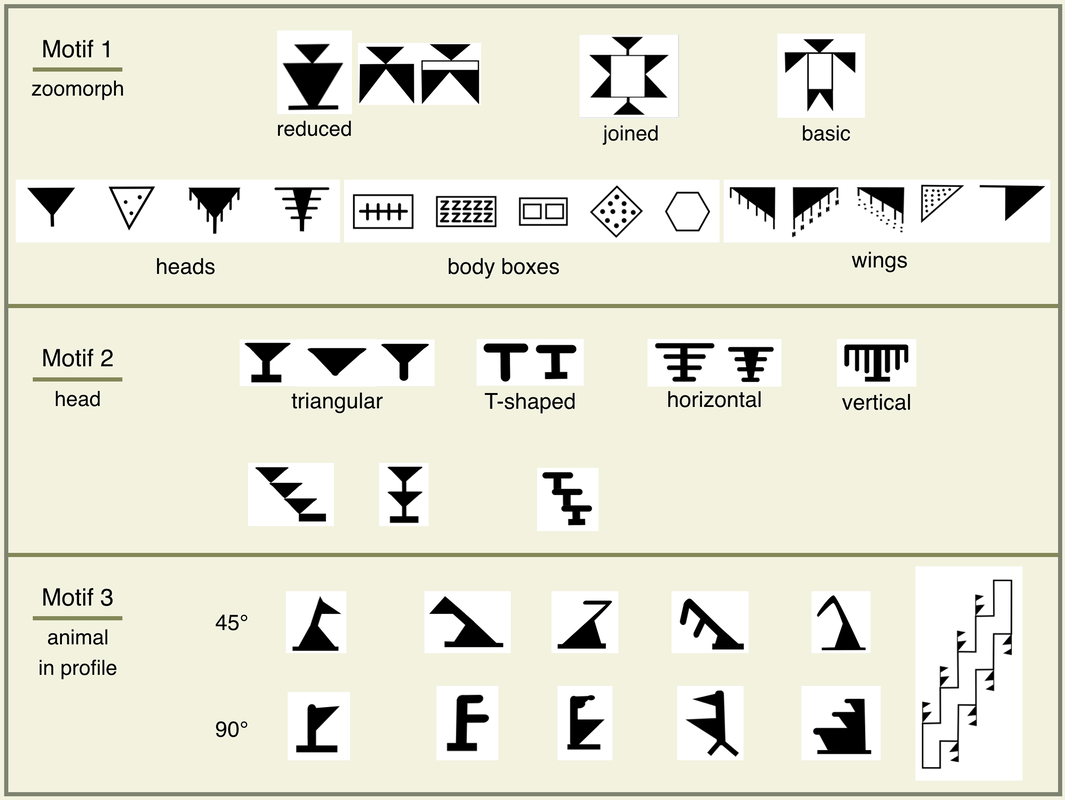

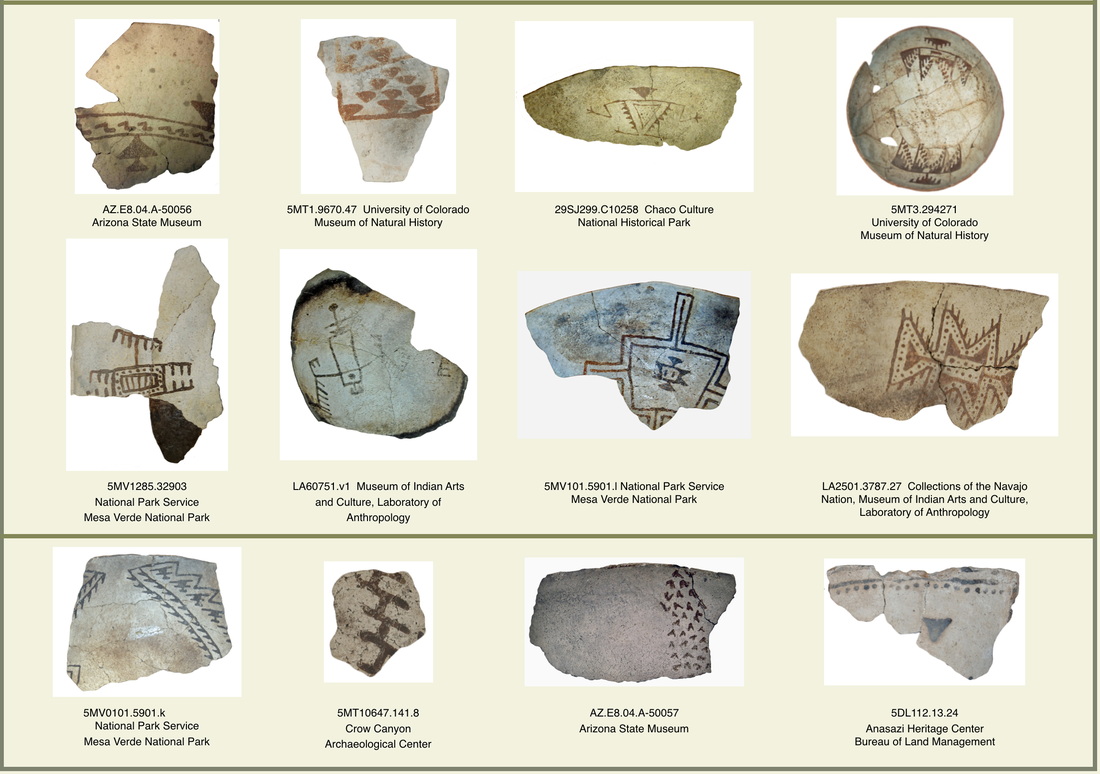

Now for the motifs. As can be seen from Figure 2, Motifs 1, 2 and 3 are shapes constructed mainly of triangles, rectangles and intersecting lines. These are not shapes found in nature - no flowers, no people, no snow-capped mountains. For years I have used nick-names for my motifs; zoomorph, head, and animal in profile. Now my research is suggesting I have to rethink this whole topic, as you will see later in my talk.

Figure 2. Stylized drawings of Motifs 1, 2 and 3, showing basic forms and common variations and layouts.

Motif 1 was depicted in three forms: reduced, joined and basic. It was individualized by the use of different styles of heads, body boxes, and wings. Motif 2 was depicted in four forms: triangular, T-shaped, horizontal line and vertical line. It achieved its limited individuality through repetition of elements such as these stepped and stacked configurations. Motif 3 was depicted in two forms: 45° and 90°. These two forms generally differed in their layouts: the 45° form was most often shown on straight lines, while the 90° form was most often shown on stepped polygons.

In order to discuss the temporal and spatial distribution of Motifs 1, 2 and 3, it will be necessary to discuss three time periods: Before, During and After the Basketmaker III period in the Four Corners Region.

In order to discuss the temporal and spatial distribution of Motifs 1, 2 and 3, it will be necessary to discuss three time periods: Before, During and After the Basketmaker III period in the Four Corners Region.

Basketmaker II Period (ca. 200 BC - 500 AD)

Before the Basketmaker III period was the Basketmaker II period, and my research indicates that a discussion of Motifs 1 and 2 actually has to start then, sometime between 200 BC and 500 AD (PMAE website:16-9-10/A2790) (Webster 2018). During that time, prehistoric weavers in the Four Corners Region produced bags, baskets and sandals which displayed several styles of Motifs 1 and 2.

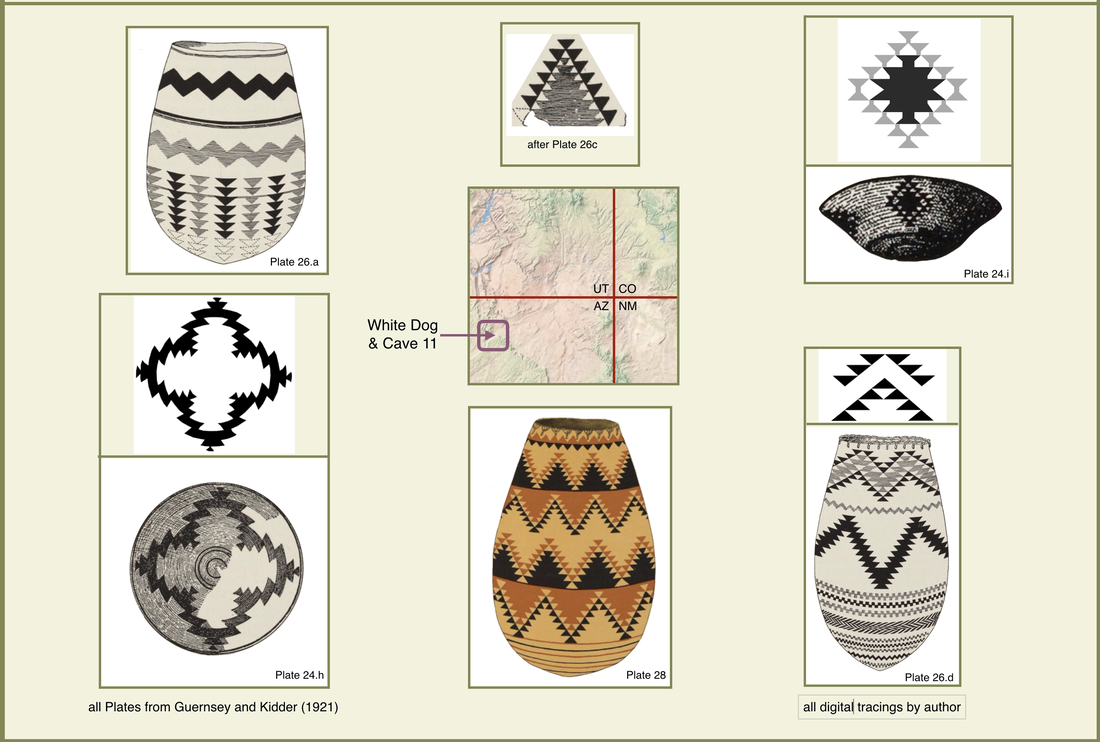

As can be seen from Figure 3 below, the Basketmaker II weavers created complex designs involving the use of zig-zag lines of parallelograms, inverted figures, and positive and negative spaces. Motif 1 Reduced was depicted both as a two-tiered figure and as a taller three- to six-tiered figure. Motif 1 Joined was depicted as two three-tiered figures which lacked a shared body box. Motif 2 served to border both the Reduced and the Joined forms of Motif 1. These bags and baskets were recovered from White Dog Cave and Cave 11 in northeast Arizona (Guernsey and Kidder 1921).

As can be seen from Figure 3 below, the Basketmaker II weavers created complex designs involving the use of zig-zag lines of parallelograms, inverted figures, and positive and negative spaces. Motif 1 Reduced was depicted both as a two-tiered figure and as a taller three- to six-tiered figure. Motif 1 Joined was depicted as two three-tiered figures which lacked a shared body box. Motif 2 served to border both the Reduced and the Joined forms of Motif 1. These bags and baskets were recovered from White Dog Cave and Cave 11 in northeast Arizona (Guernsey and Kidder 1921).

Figure 3. Examples of Motifs 1 and 2 in the Basketmaker II Period at White Dog Cave and Cave 11, Arizona.

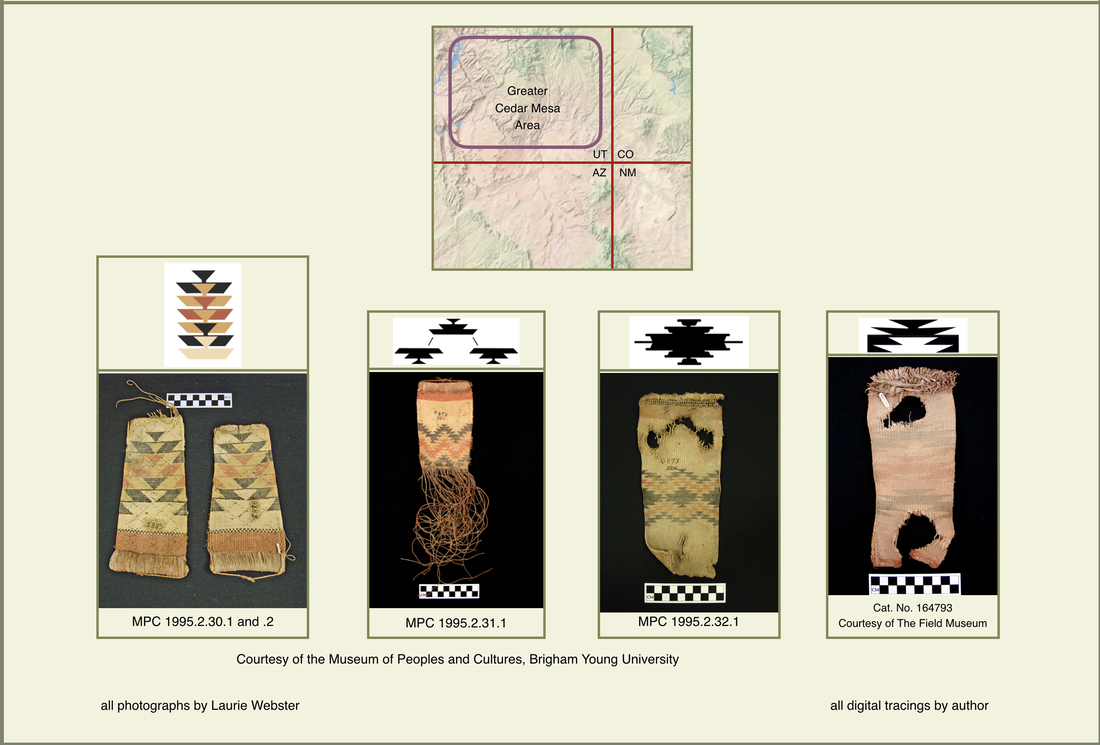

Further to the north, interlocking and nested examples of Motif 1 were depicted on sandals (Figure 4). It is likely that the use of several colors (black, red, cream, tan) imparted additional information to these textiles, which were recovered from caves in the Greater Cedar Mesa Area in southeast Utah (Cedar Mesa Perishables Project).

Figure 4. Examples of Motif 1 in the Basketmaker II Period in the Greater Cedar Mesa Area, Utah.

Basketmaker III Period (ca. 500-750 AD)

During the following BM III period, both Motifs 1 and 2 underwent significant changes from their Basketmaker II predecessors (Figure 5). When painted on bowl surfaces, they were depicted in colors of reddish brown to black. Motif 1 was reduced to a simple two-tiered figure, composed of a triangular body topped by a smaller triangular head. (top row, first three). The Joined form continued in use, but with the addition of a body box (middle row). Along with the Basic form (top row, right), all three forms were individualized by the use of variously shaped heads, appendages, and body boxes, fill patterns, and outlining.

Figure 5. Examples of Motifs 1 and 2 in the Basketmaker III Period (ca. 500-750 AD).

Motif 2 was freed from its primary position as accompaniment to Motif 1. It was expanded into the T-shape, often joined or stepped, and the horizontal and vertical line styles (bottom row). While still used in the stepped and stacked styles, it also was depicted on straight base lines, and as floating.

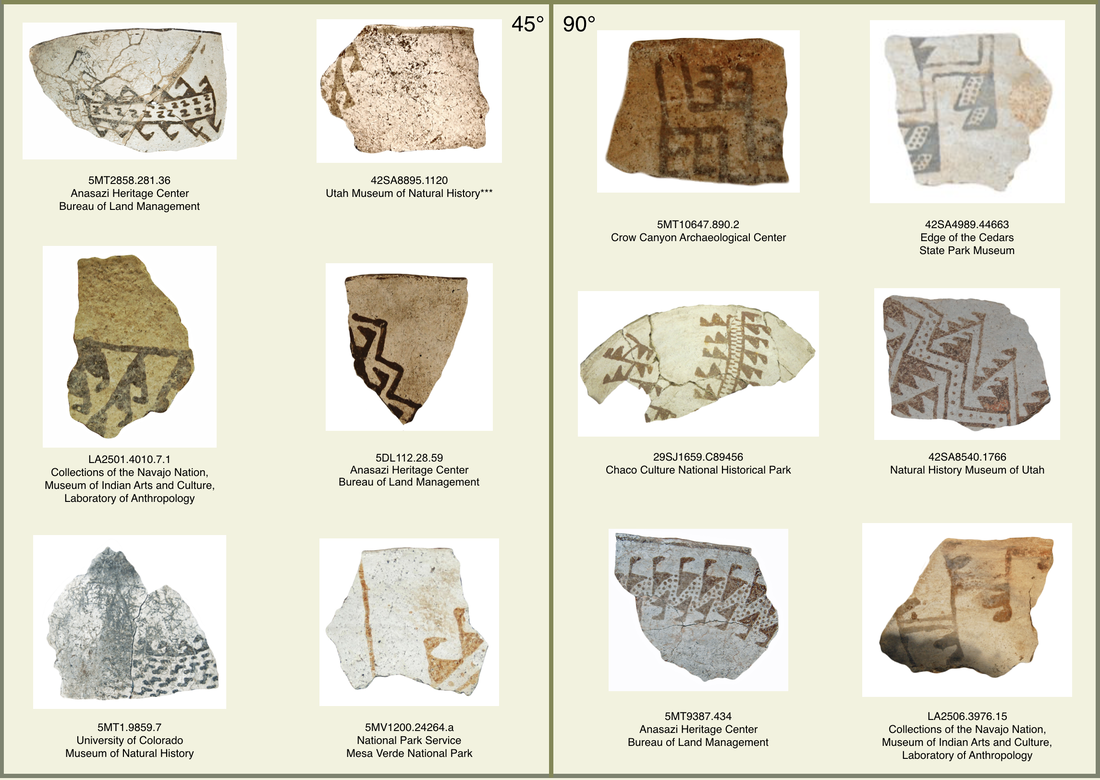

Unlike Motifs 1 and 2, Motif 3 has no known predecessor in BMII times. It seems likely, however, that the 90° Form of Motif 3 (Figure 6, right half) was developed sometime, somewhere, prior to the Basketmaker III period, because it was present on the earliest project sites with painted pottery (ca. 575). (Honeycutt 2015:16-17). The 90° form was in common use throughout the Basketmaker III period.

Unlike Motifs 1 and 2, Motif 3 has no known predecessor in BMII times. It seems likely, however, that the 90° Form of Motif 3 (Figure 6, right half) was developed sometime, somewhere, prior to the Basketmaker III period, because it was present on the earliest project sites with painted pottery (ca. 575). (Honeycutt 2015:16-17). The 90° form was in common use throughout the Basketmaker III period.

Figure 6. Examples of Motif 3 in the Basketmaker III Period (ca. 500-750 AD).

In contrast, the 45° form was developed later, sometime between 600-650, and was always far less common that the 90° form. (Figure 6, left half). During the Basketmaker III period, it reached its maximum distribution between 650-750.

Spatial Distribution of Motifs 1, 2 and 3

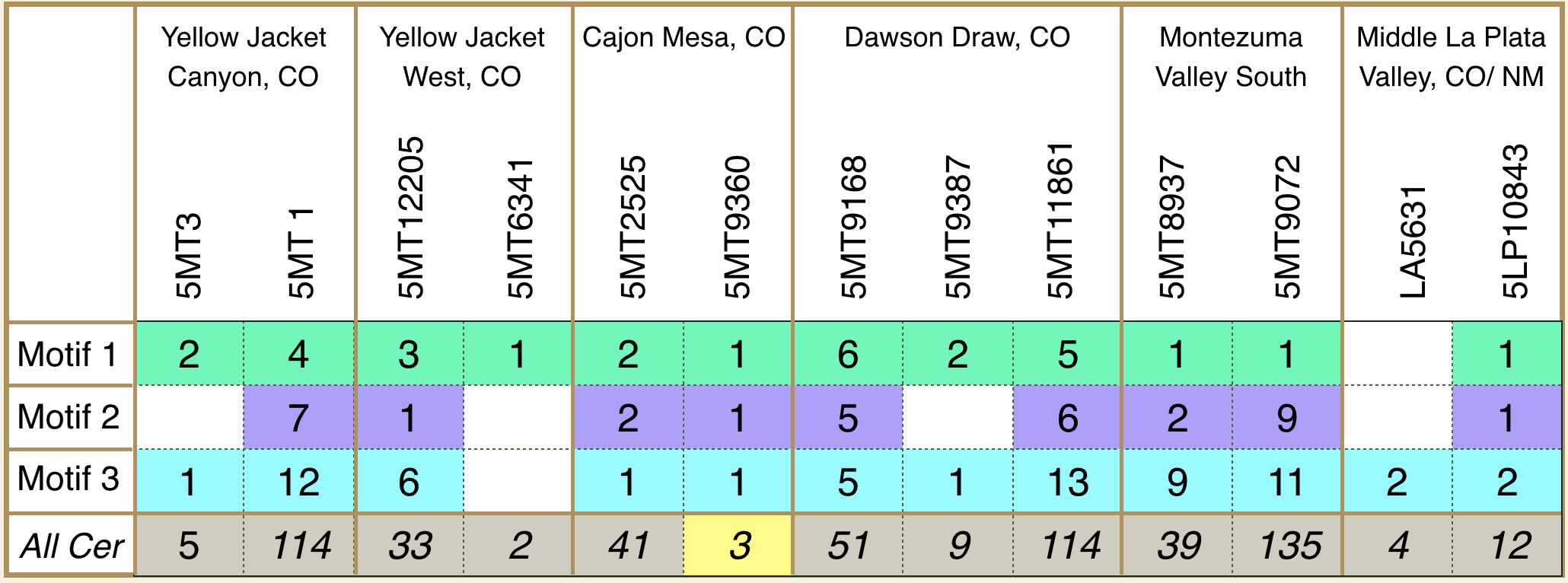

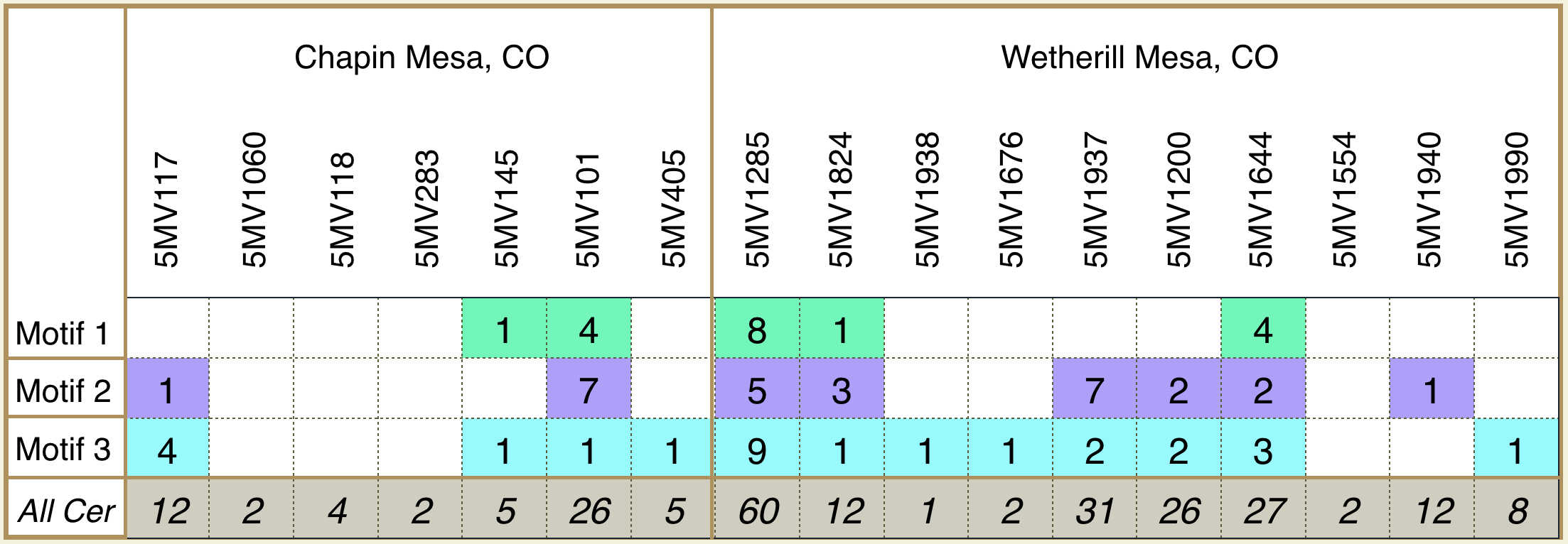

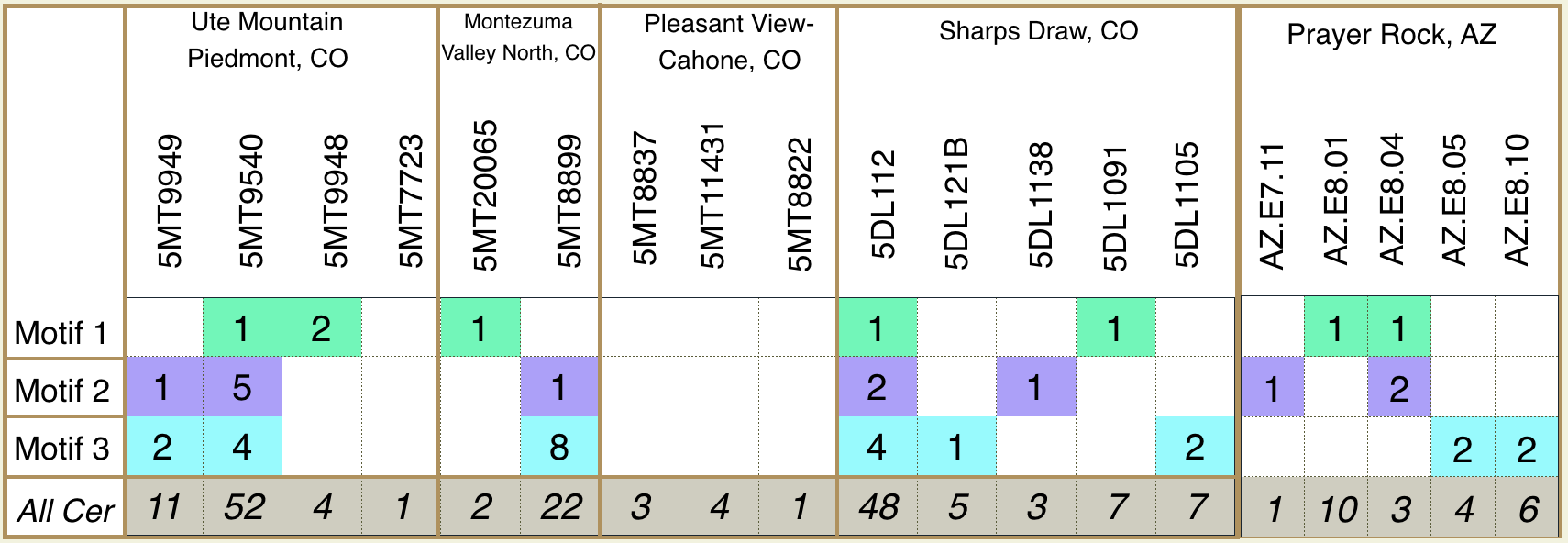

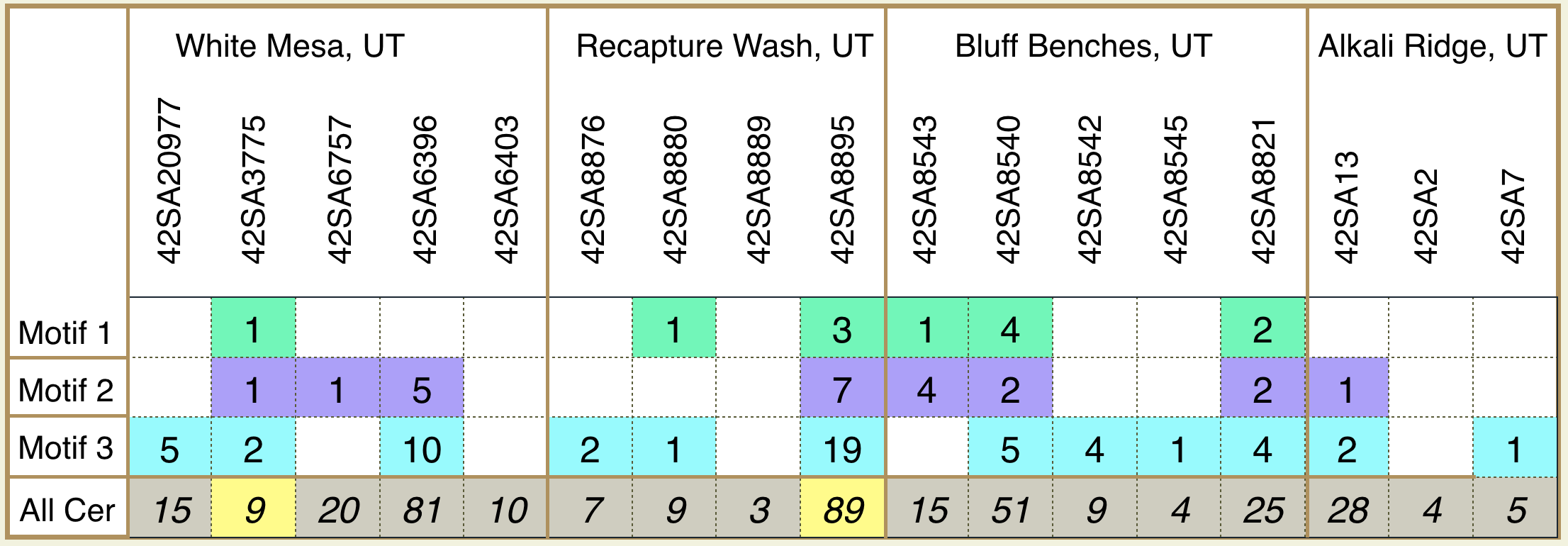

Now let's look at the spatial distribution of these three motifs in detail. Of the 32 study units, 22 contain two or more sites, and I refer to these as communities (Figure 7). Many of these are communities in the true sense of the word, containing two or more contemporaneous sites within easy walking distance of each other. For the purposes of this talk, I will be using data from these communities, which contain a total of 97 sites, and not the 11 single-site units. Also for the purposes of this talk, I will be ignoring the issue of site contemporaneity, as it is not critical to the following discussion.

Figure 7. Map showing location of all 32 project study units, with 22 multi-site units (communities) in yellow.

Beside showing the locations of the multi-site communities, Figure 7 illustrates, in a rough fashion, the distribution of Motifs 1, 2 and 3. Of the 22 communities, 19 (or 86%) contained examples of all three motifs. In other words, at an inter-community level, the motifs appear somewhat uniformly distributed. However, at an intra-community level, this is not the case. Within each of the 22 communities, one of two patterns is evident.

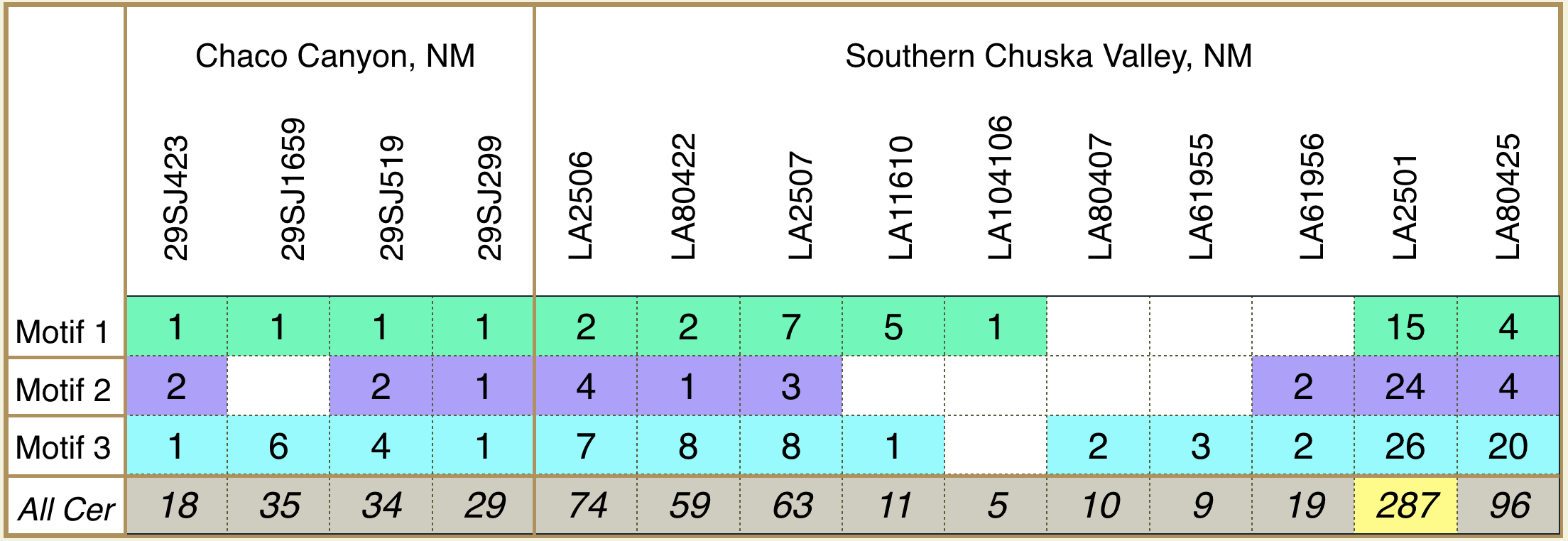

A Pattern 1 community is defined as a community in which half or more of the sites contain at least one example of all three motifs. Eight Pattern 1 communities are present in the study area: the two New Mexico communities, five Colorado communities, and the one Colorado/New Mexico community (see Figure 8). Sites containing all three motifs have as few as three and as many as 287 sherds and bowls in their total ceramic assemblages. Of the 27 Pattern 1 sites, 17 contain all three motifs, and the remaining 10 each contain at least one motif. As a result, the Pattern 1 communities contain 54% of the three motifs, even though they contain only 27% of the sites.

Figure 8. Pattern 1 Communities in New Mexico and Colorado.

A Pattern 2 community is defined as a community in which less than half of the sites contain at least one example of all three motifs. Fourteen Pattern 2 communities are present in the study area: nine Colorado communities, all four Utah communities, and the single Arizona community (see Figure 9). In these communities, a clear discrepancy exists between the sites which do not contain all three types, and those that do. Of the 70 Pattern 2 sites, only 12 contain all three motifs. Of the remaining 58 sites, 43 have one or two motifs, and 15 have none. Pattern 2 sites with all three motifs have as few as nine and as many as 89 sherds and bowls in their total ceramic assemblages. As a result, the Pattern 2 communities contain only 46% of the three motifs, even though they contain 72% of the sites.

Figure 9. Pattern 2 Communities in Colorado, Arizona and Utah.

As the present time, I don’t know why this pattern exists, but besides the usual suspects of site function and duration, I am interested in the possible effects of ritual inclusion or exclusion, the rules regarding storage of ceremonial objects, and the proximity of a great pithouse.

Late Prehistoric, Protohistoric, Historic and Modern Periods

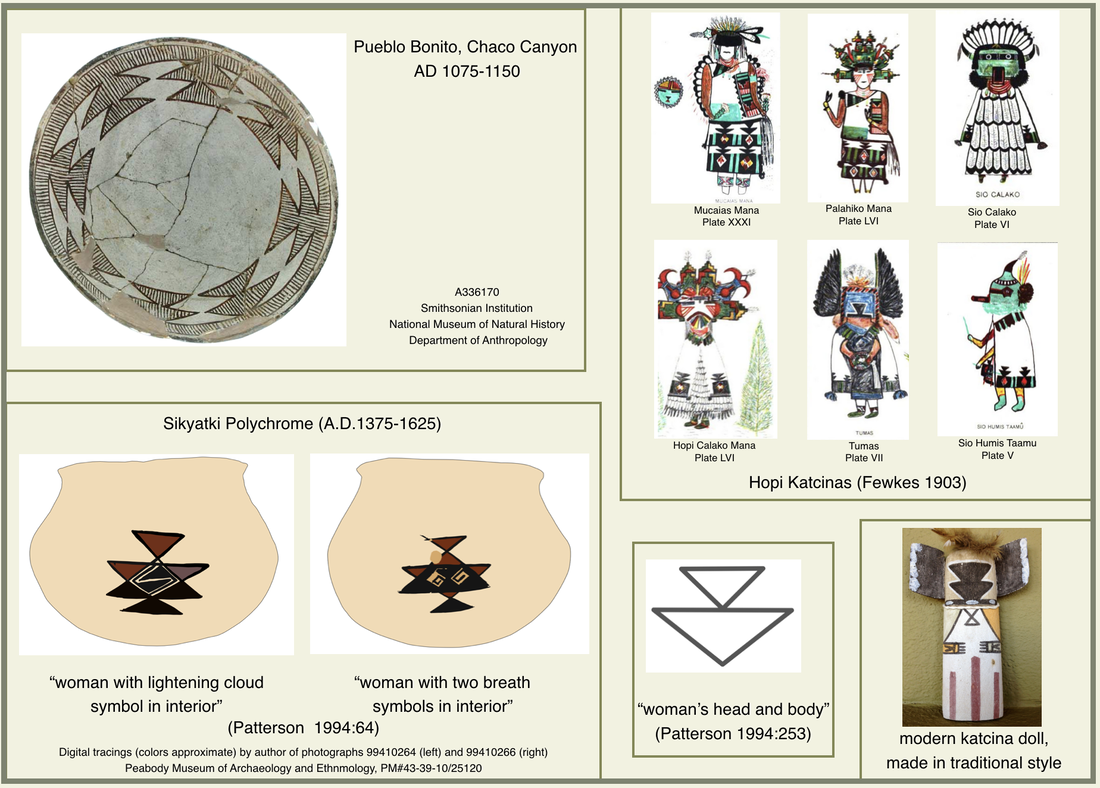

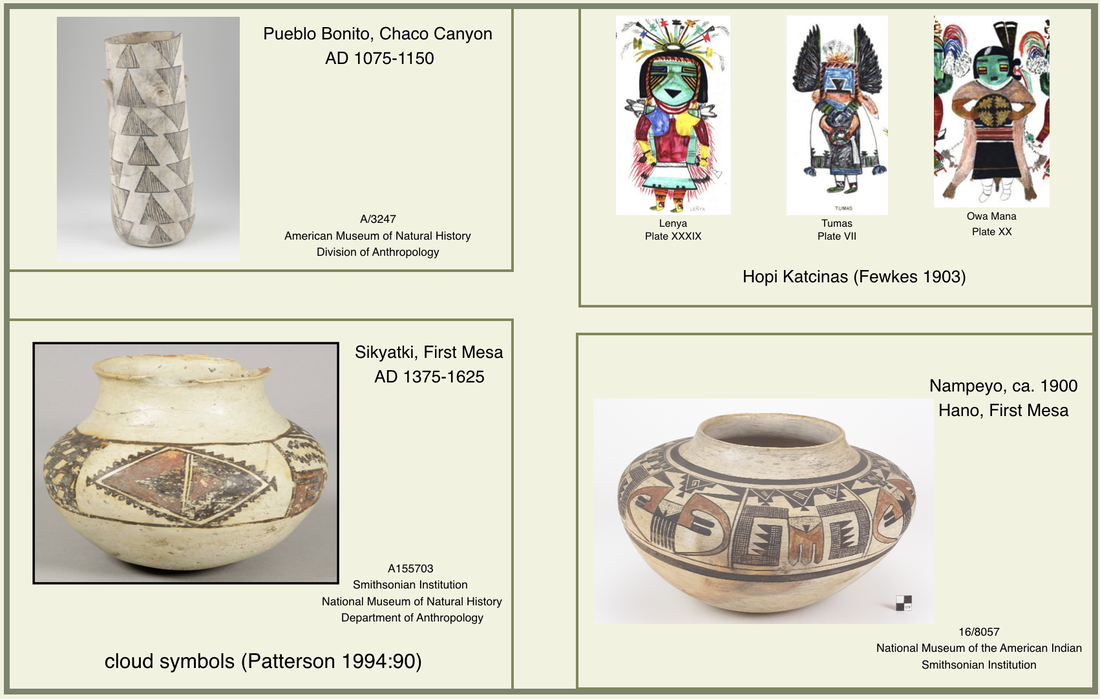

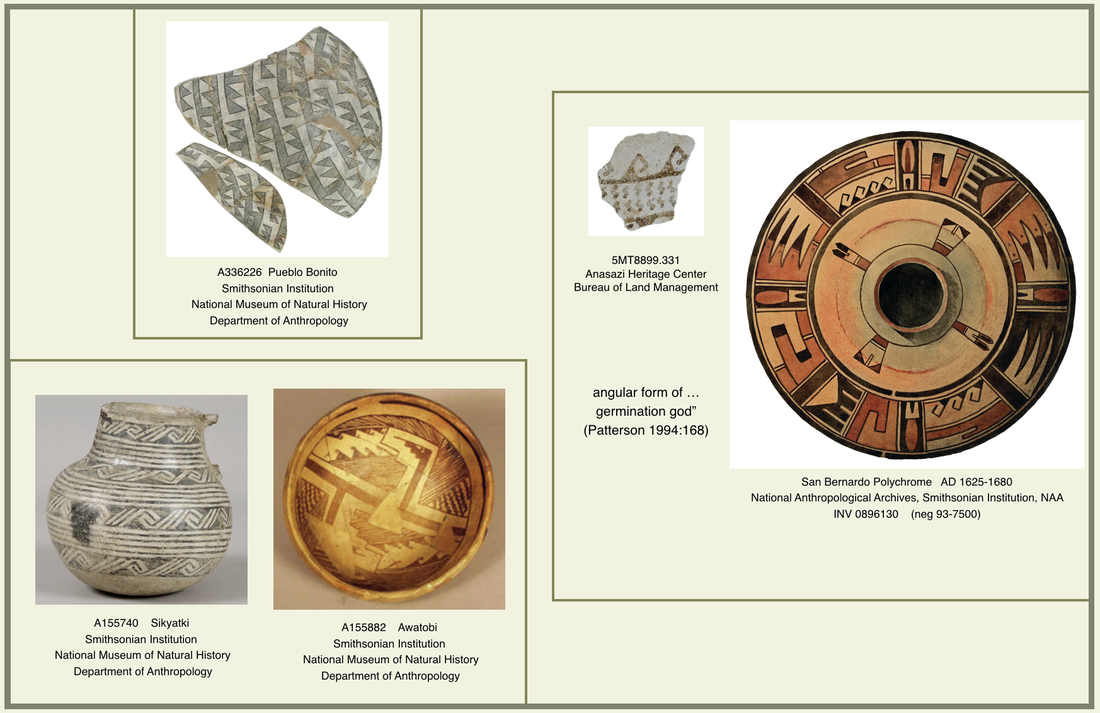

Following the Basketmaker III period, the three motifs declined in use but did not disappear entirely. In fact, they can be followed into the later Prehistoric, Protohistoric, Historic and Modern periods, as shown in the remainder of this talk. The three motifs occur on pottery at the prehistoric site of Pueblo Bonito, and at the protohistoric sites of Awatobi and Sikyatki (see Figure 10). Depictions of these motifs can also be seen on pottery, ceremonial clothing, and katcina dolls of both the historic and modern periods on the Hopi mesas.

Figure 10. Map showing location of selected post-Basketmaker III sites in the study area.

One benefit of this cultural continuity is that ethnographic work conducted by Alexander Stephen in the 1880s provides information about the meaning of Motif 1. At that time, these two jar motifs (Figure 11, lower left) were identified by a Hopi informant as meaning “woman”, and this shape (Figure 11, lower middle) was identified as representing a “woman’s head and body” (Patterson 1994:253). These are clearly examples of Motif 1 Joined and Reduced forms respectively. Does this mean that earlier depictions of these motifs also represent women? Taking it one step further back, does this mean that the Basketmaker III people were matrilineal and matrilocal like the Hopi? If so, could this form of social organization explain the ceramic distribution in Pattern 1 and Pattern 2 communities?

Figure 11. Examples of Motif 1 in the Prehistoric, Protohistoric, Historic and Modern Periods (ca. 1000-2000).

Moving on to Motif 2, we have examples of both the stacked and stepped forms in the prehistoric, protohistoric and historic periods. Stephen’s ethnographic work yielded an interpretation of what I call “stepped triangles" as being “cloud symbols” (Patterson 1994:253), though not in reference to this exact jar (Figure 12, lower left). This is an entirely different interpretation from my own, which has them identified as heads. Were they ever viewed prehistorically as heads? If so, did they later evolve into cloud symbols? Or do they retain two meanings? Or did they never refer to heads?

Figure 12. Examples of Motif 2 in the Prehistoric, Protohistoric and Historic Periods (ca. 1000-1900).

For Motif 3, both the 90° and 45° forms continued into the Pueblo II period, but after that, the 90° form appears to have dropped out of use. The 45° form can be seen on Sikyatki, Atowabi and San Bernardo ceramics. Stephen’s Hopi informant identified this jar (Figure 13, right) as displaying four examples of the “angular form of … the germination god” (Patterson 1994:63). Unlike Motifs 1 and 2, which have multiple matching examples in both the prehistoric and later periods, this form of Motif 3 is only represented by a single sherd in my data base, from a Basketmaker III site in the Dolores River Valley in Colorado.

Figure 13. Examples of Motif 3 in the Prehistoric, Protohistoric and Historic Periods (ca. 1000-1900).

Summary

In summary, Motifs 1, 2 and 3 were not exclusively Basketmaker III pottery motifs. Motifs 1 and 2 were used on textiles approximately 2,000 years ago in southeast Utah and northeast Arizona. During the Basketmaker III period, all three were depicted on pottery, but this pottery was not uniformly distributed across sites in the Four Corners Region. Since that time, the three motifs have continued in use on a variety of materials, including pottery and textiles, primarily in Hopi villages and towns in northeast Arizona.

References

Cedar Mesa Perishables Project. www.friendsofcedarmesa.org/perishablesproject

Fewkes, Jesse Walter

1903 Hopi Katcinas, drawn by native artists. Twenty-first Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology 1899-1900. Washington Government Printing Office

Guernsey, Samuel James and Alfred Vincent Kidder

1921 Basketmaker Caves of Northeastern Arizona: Report on the Explorations, 1916-17. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Vol. VIII. No. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts

Honeycutt, Linda

2015 Motifs 1-9 at Two Early Basketmaker III Sites in New Mexico. Pottery Southwest Fall 2015 Volume 31 No. 3.

Patterson, Alex

1994 Hopi Pottery Symbols. Johnson Books, Boulder

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology website

https://pmem.unix.fas.harvard.edu

Webster, Laurie D.

2013 FMNH 21704 in Five AMS Radiocarbon Dates from Perishable Artifacts from Battle Cave (Atlatl Cave) and Grand Gulch, Southeastern Utah, at the Field Museum of Natural History. A Canyonlands Natural History Association Discovery Pool Project.

Fewkes, Jesse Walter

1903 Hopi Katcinas, drawn by native artists. Twenty-first Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology 1899-1900. Washington Government Printing Office

Guernsey, Samuel James and Alfred Vincent Kidder

1921 Basketmaker Caves of Northeastern Arizona: Report on the Explorations, 1916-17. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Vol. VIII. No. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts

Honeycutt, Linda

2015 Motifs 1-9 at Two Early Basketmaker III Sites in New Mexico. Pottery Southwest Fall 2015 Volume 31 No. 3.

Patterson, Alex

1994 Hopi Pottery Symbols. Johnson Books, Boulder

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology website

https://pmem.unix.fas.harvard.edu

Webster, Laurie D.

2013 FMNH 21704 in Five AMS Radiocarbon Dates from Perishable Artifacts from Battle Cave (Atlatl Cave) and Grand Gulch, Southeastern Utah, at the Field Museum of Natural History. A Canyonlands Natural History Association Discovery Pool Project.